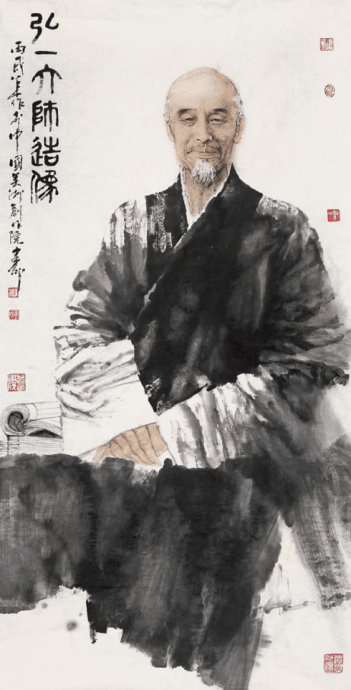

Master Hongyi (弘一大师, October 23, 1880 – October 13, 1942) was originally named Li Shutong (李叔同) and was born into a prosperous family in the bustling northern city of Tianjin on October 23, 1880. The family, originally hailing from Hongdong County, Shanxi, had relocated to Tianjin during the Ming Dynasty.

Li Shutong’s grandfather, a prosperous banker and salt merchant, and his father, Li Shizhen (李世珍), a scholar deeply immersed in Chan Buddhism and the teachings of Ming Neo-Confucian philosopher Wang Yangming (1472-1529), reflected the family’s intellectual and financial standing.

In contrast, Li Shutong’s mother had a modest upbringing as the daughter of a farmer in Pinghu, Zhejiang Province. She became Li Shizhen’s fourth wife in their multi-courtyard household, marrying him at the age of 20 when he was 68.

Tragically, Master Hongyi’s father passed away when he was just four years old. Subsequently, his mother faced challenges in maintaining her position within the complex dynamics of the household while residing under her eldest son’s roof. Fortunately, Li Shutong found support from two of his elder half-brothers during his early years, allowing him to access a quality education and a firm foundation in the Confucian classics.

Influenced by his formative experiences, Li Shutong eloquently expressed a profound perspective on life through poetry at the tender age of 15, capturing the fleeting nature of wealth and honor: “Life is truly like the setting sun on the western hills; wealth and nobility are as transient as frost on the grass.” His personal life, marked by an unconventional marriage, served as a poignant reflection of the internal conflict between societal expectations and his genuine affections.

Li Shutong’s participation in the Hundred Days’ Reform and subsequent rumors prompted his relocation to Shanghai, where he thrived in the dynamic literary scene. Becoming a prominent figure in Shanghai’s cosmopolitan lifestyle, he joined the Chengnan Wenshe and co-founded the “Five Friends of Tianya.”

His impact extended beyond literature. Collaborating with the painter Ren Bonian, he established the Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Association, marking a pivotal moment in Chinese art history. Li Shutong’s engagement in Liyuan activities showcased his versatility as a performer in plays such as “Bai Shuitan” and “Huang Tianba.”

Li Shutong’s literary repertoire included numerous poems and songs, among them the renowned poem “Farewell” (《送别》, Song Bie), which later inspired the widely sung “The Farewell Song” (《送别歌》, Song Bie Ge).

The Farewell Song

Outside the long pavilion, along the ancient route, fragrant green grass joins the sky,

The evening wind caressing willow trees, the sound of the flute piercing the heart, sunset over mountains beyond mountains.

At the brink of the sky, at the corners of the earth, my familiar friends wander in loneliness and far from home,

One more ladle of wine to conclude the little happiness that remains; don’t have any sad dreams tonight.

However, Li Shutong’s life underwent a profound transformation. Confronted with personal and financial challenges, he voluntarily entered a self-imposed exile in Japan. The success of the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 further complicated his circumstances, resulting in financial ruin. Undeterred by these setbacks, Li Shutong maintained composure and supported his family by teaching in Tianjin and Shanghai.

His teaching career, notably at Zhejiang First Teachers’ College, left an indelible mark. Li Shutong played a pivotal role in introducing Western painting to China, earning him the title of the forefather of Chinese oil painting. As the first Chinese art educator to incorporate nude models in his painting classes and introduce Western music to China, his influence was far-reaching. Some of his personally groomed students, including contemporary Chinese artist, educator, and musician Feng Zikai (丰子恺), and Singaporean artist Chen Wenxi (陳文希), went on to become accomplished artists in their own right. His impact on students, such as the renowned painters Pan Tianshou and Shen Benqian, underscored his lasting influence.

During this period, Li Shutong delved deeper into Buddhism. In 1916, he embarked on a 21-day fast at a temple in Hangzhou to experience aspects of the spiritual path. This experience prompted his decision to embrace the ordained life, leading to his monastic vows at Hupao Temple. His disciplined lifestyle, which included fasting therapy for deeper insights, marked a significant spiritual transformation.

Li Shutong’s transition from a worldly existence to a monk, detailed in a letter to his second wife, Yu, reflected his detachment from transient fame and wealth. His decision to leave behind a worldly life for monastic vows occurred only a month after joining the Order. He was known by the monastic names Yanyin (演音) and Hongyi (弘一) after undergoing full ordination rites at Lingyinsi, the largest monastery in Hangzhou.

His departure, though painful for those close to him, exemplified Master Hongyi’s profound understanding of Buddhism. In a conversation with his second wife, he elucidated the nature of love, defining it as compassion, aligned with Buddhist teachings that emphasize letting go of attachment and cultivating compassion.

Master Hongyi’s transformation from the proud and arrogant Li Shutong to a humble and receptive teacher was evident in his approach to teaching Dharma. Contrary to expectations of flawless mastery, Master Hongyi sought feedback from student monks and welcomed constructive criticism without defending himself.

By early 1942, the toll of austerities and fasts began affecting Master Hongyi’s health, and by mid-May, his condition deteriorated rapidly.

Three days before his passing at Busi Temple in Quanzhou, Fujian Province, on October 13, 1942, Master Hongyi inscribed his final calligraphic strokes, creating the work known as “Sorrow and Joy Comingle,” “Worldly Sorrows and Joy Are Intertwined,” or “Sorrow or Joy Are Inextricably Bound to Each Other” (《悲欣交集》, Beixin jiaoji).

Master Hongyi’s philosophical framework posited three distinct stages in human life: material, intellectual, and spiritual. The material phase pertains to mundane existence, the intellectual phase characterizes the life of ordinary intellectuals, while the spiritual phase encompasses the religious realm.

Material, intellectual, spiritual; beauty, profundity, deity. These concepts are intricately tied to the principles of abstinence, composure, and wisdom in Buddhism.

Abstinence, in this context, denotes the renunciation of materialistic pursuits. Composure signifies the practice of deep meditation—tranquil and remote—a path that ultimately leads to the attainment of wisdom. The imagery of Venerable Hongyi experiencing both sorrow and joy (欣) symbolizes the dynamic interplay between these various dimensions of life.

Li Shutong: From Prodigy to Monk – A Journey Beyond Wealth and Artistry

Link:Li Shutong: From Prodigy to Monk – A Journey Beyond Wealth and Artistry