In the Mountain Tree chapter of the ancient Taoist classic Zhuangzi, there’s a simple yet profound story:

A man was crossing a river in a small boat when he noticed another boat drifting straight toward him. He shouted several times to warn the oncoming boat, but received no reply. Furious, he began cursing the other “reckless” person. But when the boats collided, he realized the other vessel was completely empty. In that moment, his anger vanished into thin air.

This story reveals a timeless truth: Often, what triggers our anger isn’t real harm but our judgment about the intention behind an event—our belief that someone shouldn’t have acted a certain way, or that people like that shouldn’t exist.

Imagine the same situation, but this time with a person steering the other boat. Most of us would react with outrage: “What’s wrong with you? Watch where you’re going!” A conflict would likely erupt. But when we know the boat is empty, we simply steer around it and move on.

This is beautifully explained in psychology by the ABC model:

- A stands for the Activating event

- B is our Belief about the event

- C is the Consequence—our emotional response

It’s not the event itself that causes our reaction, but how we interpret it. Change your mindset, and your entire emotional response changes with it.

“The weak blame, the strong adjust, the wise let go.”

How you choose to interpret the world shapes the emotional and spiritual life you live.

Zhuangzi’s parable invites us to practice a mental shift: what if we saw others as “empty boats”? When a coworker unintentionally bumps into you, instead of assuming hostility, think, “Maybe they were just distracted.” When a friend speaks harshly, perhaps they’re struggling with something you don’t know. Instead of reacting with pain or revenge, consider that it may not have been personal.

Seeing others as “empty boats” helps us release resentment, practice compassion, and expand our emotional resilience. It allows us to heal ourselves faster, without getting trapped in cycles of blame and victimhood.

German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer once said:

“To be angry at someone’s behavior is as foolish as being angry at a rock blocking your path.”

True wisdom lies in seeing through the illusion of control, and responding with tolerance rather than judgment.

When life doesn’t go our way, it’s easy to fall into the trap of self-pity: “Why is this happening to me?” But such thoughts only darken our mood and invite more misery.

The real shift happens when we stop blaming others and start examining our own mindset. By applying the “Empty Boat” perspective, we reduce conflict, soothe emotional storms, and gain a wider, calmer view of life. This isn’t just emotional regulation—it’s a deeper level of personal growth.

Zhuangzi also wrote:

“If a person can empty themselves and move through the world with humility, who can harm them?”

When we’re too attached to ego—too quick to feel offended, too focused on saving face—we inevitably clash with others. But if we release pride, prejudice, and the need to control, we become unshakable. No one can truly hurt us when we no longer take things personally.

Our mindset is the foundation of how we face adversity. Approach life with a peaceful, open heart, and life will respond in kind. Let go of the need for constant validation. Don’t let others’ words disturb your inner calm.

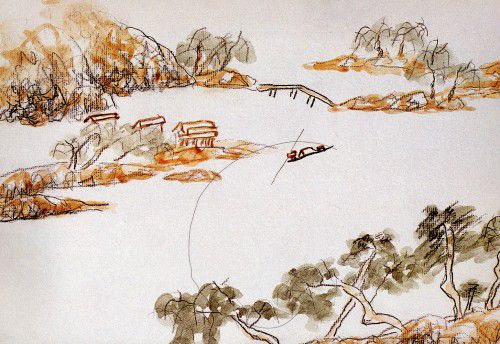

The journey of life is like sailing through mist—we never know what lies ahead. Complaining or getting angry doesn’t change reality; it only slows us down. But when we practice acceptance and face life with serenity, we go farther, and with greater ease.

Imagine all the unpleasant people or events in your life as “empty boats.” Let go of resentment and emotional baggage. You’ll find that forgiveness is not weakness, but a deep, penetrating wisdom. No longer a slave to your emotions, you become the true master of your mind.

May you carry an empty and serene heart, navigating life’s storms with grace, and holding on to peace amid the noise of the world.