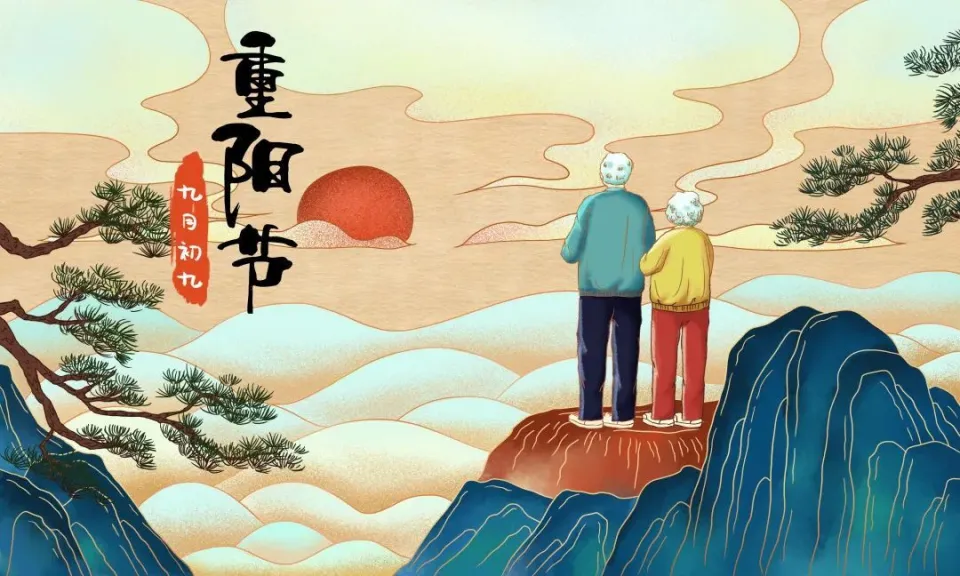

The Double Ninth Festival, also known as Chongyang Festival, falls on the ninth day of the ninth lunar month each year. In 2024, this special day is observed on October 10th. In ancient Chinese philosophy, as referenced in the I Ching, the number “nine” is considered a yang number, symbolizing strength and vitality. The festival’s name, “Double Ninth” or “Chongyang,” refers to the doubling of this powerful number, representing longevity and blessings.

The pronunciation of “九九” (jiǔ jiǔ) sounds similar to “久久,” which means “long-lasting.” On this day, as autumn unfolds with its vivid hues, people gather to hike, enjoy the red cornelian cherries in bloom, eat Chongyang cakes, and drink Chongyang wine, all while offering prayers for well-being and longevity. The number nine, being the highest single-digit odd number, is symbolic of long life, carrying with it the wishes of good health and longevity for the elderly. As time passes and human lives inevitably age, nature remains timeless, and we all must face the farewells that are a part of life.

Chongyang Festival is one of China’s most significant traditional holidays, and over the centuries, its customs have continued to thrive. People climb to high places to seek blessings, enjoy autumn scenery, appreciate chrysanthemums, and wear cornelian cherry (茱萸) as part of the ancient traditions. The festival has also become China’s officially designated Senior Citizens’ Day, a reflection of the nation’s cultural emphasis on honoring the elderly, with filial piety at the heart of the celebrations. The deep respect for elders, a core Chinese value, is encapsulated in the tradition of 孝 (xiào), which has remained unchanged through the ages.

Historical records of Chongyang customs date back to Lüshi Chunqiu, and by the Han dynasty, it became common for people to wear cornelian cherries and drink chrysanthemum wine during the festival in hopes of promoting longevity. The chrysanthemum, admired for its elegance and resilience to frost, has long symbolized the virtuous gentleman in Chinese culture. During Chongyang, chrysanthemums bloom in abundance, and the festival would be incomplete without them. As the saying goes, “Without chrysanthemums, there is no Chongyang.” Ancient people lit chrysanthemum lanterns, decorated the streets with flower displays, and gathered to admire the blossoms in the evening, adding a special charm to the festival.

Tao Yuanming, one of China’s most beloved poets, wrote in the preface to Leisure at the Ninth Day: “In my leisure, I cherish the name of the Double Ninth Festival. With the garden full of chrysanthemums, I long for the wine but find none; so I simply sip the nine flowers in their essence.”

This imagery beautifully captures the festival spirit of sipping wine infused with chrysanthemum petals, a practice believed to preserve health and vitality. Wine has always been a key part of festive celebrations, and during Chongyang, chrysanthemum wine is essential. This traditional drink is believed to ward off misfortune and bring longevity.

The festival’s atmosphere is enhanced by the vibrant scenery of autumn. As the hills are covered in yellow flowers, one can imagine the joy of gathering with friends, sharing a drink, and admiring the beauty of chrysanthemums. This sense of togetherness is echoed in the works of Tang dynasty poet Meng Haoran, who described the simple pleasures of sitting with old friends by the window, drinking wine, and chatting while watching the lush vegetable garden outside. Such moments, rich in warmth and simplicity, remind us of the importance of human connection and the passage of time.

A key custom during Chongyang is wearing cornelian cherry. This tradition was especially popular during the Tang dynasty, as people believed that wearing these fruits could protect them from misfortune.

Cornelian cherries were worn on the head, the arm, or carried in sachets, serving as symbols of protection and unity among family and friends. The poet Wang Wei famously captured this sentiment in his poem Thinking of My Brothers on the Double Ninth:

“Alone, a stranger in a foreign land,

I long for my kin on every holiday.

I know my brothers are climbing high with cornelian cherries,

But there is one less person among them.”

His words reflect the deep homesickness and yearning for family, feelings that resonate with many who are far from home during important festivals.

Another significant tradition is eating flower cakes during Chongyang. The word “糕” (cake) sounds like “高” (high), and eating these cakes symbolizes the desire for life to “rise to new heights.” On the morning of Chongyang, mothers place small cakes on their children’s foreheads while whispering prayers for their health and safety, a heartwarming expression of parental love.

As autumn progresses and the white dew turns to frost, people celebrate the Double Ninth Festival by eating flower cakes, climbing to high places, and admiring the red leaves that blanket the hills. These simple yet profound traditions deepen the connection to nature and soften the heart’s longing for home.

The Chongyang Festival is not just a time to honor the elderly but also a celebration of the timeless values of family, respect, and filial piety. As families gather to enjoy the view from high hills and savor these precious moments together, they strengthen the bonds of kinship, appreciating the blessings of health, longevity, and the beauty of life’s passing seasons.

Photos From: https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20241011A03NUI00