You might not realize it, but this is the true power of prayer—it’s not just asking for blessings; it is awakening an internal system within you that says, “I can keep going.”

Every sincere moment of prayer leaves an imprint on the mind. This is not spiritual poetry or wishful thinking; it is a pattern repeatedly observed through MRI scans, neuroimaging, and psychological research. Each second spent in focused, quiet prayer is an opportunity to “turn on a light” in the brain—helping us become steadier, clearer, and more resilient.

Scientists were once skeptical. But the evidence surprised them.

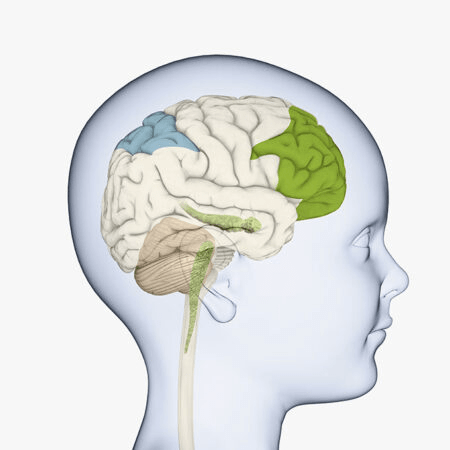

When a person enters a state of deep, focused prayer, activity in the prefrontal cortex increases. This is the part of the brain responsible for attention, judgment, emotional regulation, and self-control—the “driver’s seat” of the mind. Prayer helps us return to that seat, especially when life feels overwhelming.

At the same time, activity in the amygdala—the brain’s alarm system—tends to decrease. This region governs fear, anxiety, and the fight-or-flight response. When it is overstimulated, we feel tense, reactive, and out of control. Prayer appears to gently quiet this system, creating inner space to breathe, reflect, and choose more wisely.

This is not merely a mental effect—it is a physical response of the nervous system.

Research also suggests that heartfelt prayer—prayer infused with sincerity and emotion—is especially powerful. Compared to mechanical repetition, it more strongly activates brain regions associated with language, empathy, connection, and self-awareness, including the temporoparietal junction, anterior cingulate cortex, and medial prefrontal cortex. These areas shape how we relate to ourselves, to others, and to life itself.

In simple terms, honest prayer becomes a process of emotional clearing and inner reorganization.

When practiced regularly, these brain responses do something remarkable: they form new neural pathways. Like carving a well-worn trail through a forest, prayer creates a reliable inner path—a place of stability we can return to during moments of fear, grief, or confusion. The more often we walk this path, the easier it becomes to find our way back to calm.

Prayer is not the same as meditation. While both reduce stress and sharpen focus, prayer carries an added element: relationship. Prayer involves trust, dialogue, and the felt sense that we are not alone. This activates neural systems related to connection, attachment, and belonging—deep human needs that meditation alone does not always engage.

This may explain why, at the edge of emotional collapse, a simple, sincere prayer can sometimes bring someone back from the brink. The problem may not disappear—but the mind, heart, and body momentarily realign. A quiet strength returns. I can get through this.

What Prayer Does—Inside and Out

- Activates the Prefrontal Cortex

Strengthens clarity, emotional balance, and self-control. - Calms the Amygdala

Lowers fear and stress responses, restoring inner quiet. - Builds Emotional Resilience

Repeated prayer forms neural pathways that support stability over time. - Fosters Connection and Trust

Engages social and emotional brain systems through relationship and sincerity.

Sincere prayer may be one of the most gentle, natural, and powerful “built-in reset systems” we possess.

So when was the last time you prayed—not out of habit, but from the heart?

Have you ever noticed how your body softened afterward, how tension quietly released?

That wasn’t imagination.

That was your mind and nervous system responding to something deeply human—and deeply real.