Watching a beloved companion waste away, writhe in pain, or cry out in distress is never easy. It is heartbreaking to see a once-vibrant being—one who once leaped over fallen trees, climbed steep inclines, or joyfully bounded through snowy mountains—struggle to stand, only to lose that ability altogether. Dying is a process in which the body gradually ceases to function, and eventually, stops completely. It is neither a pleasant sight nor a pleasant smell, yet it is a natural part of life.

When a human forms a bond with another living being—whether through adoption, inheritance, or as a gift—they take on a profound responsibility. Caring for that being in sickness and health, until death arrives, is part of that commitment. The true tough decision is not to end their life prematurely, but to provide palliative and hospice care, ensuring they are comforted with love and presence in their final days. Accompanying them on their journey to death with compassion—rather than ending their life or outsourcing the act—is the ultimate expression of devotion and responsibility.

Is euthanasia the right choice for an aging and dying pet? Buddhist disciple Dani Tuji Rinpoche reflects on his experiences with his animal companions, sharing insights into their passing and his response to common beliefs about what a Buddhist should do when witnessing the suffering of a beloved animal.

In 2008, my wife Deb and I had a conversation with Zhaxi Zhuoma Rinpoche and Lama Puti about whether euthanasia was a compassionate choice to end an animal companion’s suffering when it seemed unbearable. They explained that ending an animal’s life prematurely denies them the opportunity to work through their karma, potentially leading to a less favorable rebirth. This perspective resonated with me then, and it still does today. It also reframes the way we view our responsibilities toward our animal companions, deepening our understanding of the care and presence we owe them in their final moments.

At this point I want to describe Chaco’s journey.

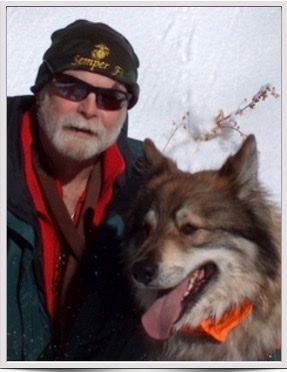

Chaco came to us as a Wolf-Malamute pup and lived out his life in our care. Magnificent is an inadequate term to try to provide a sense of who he was in this lifetime but he was all that and more. I won’t bore the reader with tales of our adventures in the mountains of northern New Mexico just outside of Taos. Suffice it to say that we ranged far and wide.

I came home one day after a thunderstorm to find Chaco limping. The gate had been opened by Dharma a female heeler that had lived across the street but who had spent most of the time playing with Chaco through the fence. When her humans moved she stayed. She was totally freaked out by thunder, fireworks, etc. and had chewed open chain link fence gates, butted down wooden gates, and more to run free from the thunder. She and Chaco had run free for some time so I thought he might have sprained something.

After a few days of limping I took Chaco to the vet’s for x-rays. The pain and gimpiness were associated with a tumor that was osteosarcoma. I drove Chaco to Colorado Canine Orthopedics & Rehab in Colorado Springs. A biopsy confirmed the diagnosis and a surgery to remove his left rear leg at the hip was scheduled. The surgery went well and Chaco regained most of his mobility and soon was running with the other dogs.

We knew he would never recover as the cancer had spread to his lungs so we wanted to do everything we could to make him comfortable. We tried chemo but stopped it when there was no sign of improvement. We enjoyed a few months of fairly normal outdoor activities and then entered the lasts stage, a period where you do things for the last time. At the beginning of this stage you may not be aware that you and your companion are doing something for the last time until you try to do it again and cannot. It becomes a great lesson in being in the moment because now you know that what you are doing may be the last time you ever do it and those activities take on a special meaning. [My perspective is that we never know for sure when we’ll die and so every moment should be lived that way. I’m a long way from being there all the time but some things just seem to demand attention.]

After the lasts comes the slide that carries us all to the same end. Chaco reached the point where his rear leg wasn’t dependable. We tried a wheelchair but that wasn’t appropriate for the circumstances, so we used a sling to support his body while he ambulated with his front legs. He quickly transitioned to wanting to be outside most of the time – he used to sleep in the snow – so we accommodated that. For several weeks Chaco and I would go out into the sage, have long conversations and sleep. When he totally lost his mobility I either dragged a sleeping bag with him on it or carried him.

His last night we were inside and he was lying in Deb’s lap. I went to take a nap and Deb woke me to tell me that Chaco had passed. He died in her arms peacefully, completing that lifetime in the animal realm.

We said mantras and did mudras and then laid him in the grave I had prepared. There is nothing like such an experience to show you how strong attachments can be to others and to self. And if there was difficulty in fearing impermanence this type of event can help you re-examine that subject.

I believed then as I do now that we had done our best for Chaco. I failed miserably with Skanda.

At eight weeks the Brazilian Mastiff puppy weighed 18 pounds. We chose the name Skanda because we thought that he would become the protector for the two remaining dogs, Lyla and Dharma. He grew rapidly, was seriously attached to Deb, and too big and strong for his good. At the beginning of adulthood, he had torn both ACL’s and, due to his size, our vet recommended the repair that Colorado Canine did that involved repositioning his tibial plateau and securing it with a plate and screws. The first operation went so well that the second could be done earlier than expected. Then came about two months of restricted activity and that meant he had to be on leash anytime he was outside. That is easier said than done but we did our best and he made it through his recovery.

Yes, osteosarcoma once more, same prognosis and no surgical option. One problem with osteosarcoma is that once it reveals itself with a tumor it has already spread and all that’s left is to try to make the dying as comfortable as possible.Life with a canine companion that weighs about 170 pounds and is fiercely protective can be challenging. Around Deb Skanda was nothing but a drooling pool of love but any sense that she was in need of protection and the transformation was dramatic. So, we took precautions and adapted. My approach was to treat him as if he had PTSD and to make sure he was shielded from as much of the triggers associated with PTSD as possible. And life was good…until he developed a tumor on his left front leg.

Skanda had a selection of pain meds that helped but after a month or so the pain in his foreleg made walking too difficult. We had added cannabis oil to his regimen and that seemed to help. His decline was fairly rapid: reduced mobility then virtually none; decreased appetite; obvious signs of distress; sleeping most of the day; incontinence. The tumor on his leg increased in size, the leg swelled with edema, his foot swelled until the skin between the toes began to open and his foot began to putrefy. At this point he would only drink a little water and take the CBD oil straight from the dropper. He refused meds, food and then treats. As his foot worsened the conversation turned to euthanasia. Bottom line is that I was weak, our vet came to the house and administered the drugs and Skanda appeared to pass peacefully. His remains were placed near Chaco’s with appropriate ceremony..

In Revealing the Truth, a book written by Shi Zheng Hui about her experiences during the twelve years lived in close proximity to H. H. Dorje Chang Buddha III I read a passage that I hoped might apply to euthanasia. In the passage Jun Ma an elderly Great Dane was taken to hospital for treatment but died that afternoon. In my strong desire to find a way to think that Skanda’s euthanasia might have been alright under the circumstances I contacted H.E. Denma Tsemang Longzhi Rinpoche to ask if the passage in the book meant that Jun Ma had been euthanized. The reply I received reiterated that there were no circumstances that would allow for euthanasia.

During 2018 I provided and Deb participated in hospice and palliative care for both Dharma and Lyla. Dharma created a nesting space in the sage and spent her last days there. Once she settled in she refused food and would only take a little water. She seemed to indicate that she would prefer being left alone so the last two or three days we would check on her and adjust her sun shade. She died with no apparent distress and was buried next to Chaco with appropriate ceremony and ritual.

Several months later Lyla passed away with no indication of distress. I checked on her in the early morning and she was fine then about half an hour later she was dead. She was buried next to her longtime companion Dharma.

The dogs with which we live have all been given a Blue Dharma pill to help them find the Dharma and all have taken refuge. Those that have passed were buried with recitations of The Buddha Speaks of Amitabha Sutra.

There are things to consider when adopting or otherwise finding a new canine companion. Your age, their life expectancy, your physical condition, their size, your life expectancy, their life after your death.

source: https://holyvajrasana.org/articles/the-issue-of-euthanasia-for-buddhists-and-the-pets-with-which-they-live