Recently, the animated film Nezha 2 has become incredibly popular, reaching the top spot in global box office earnings for animated movies. While many believe Nezha is a character from Chinese mythology, his origins can actually be traced back to Buddhist scriptures.

Nezha’s name first appeared in Vajrayana Buddhist texts, where he is associated with the role of a Dharma protector. He is described as the third son of Vaisravana, one of the Four Heavenly Kings. According to The Ritual of Vaisravana, “The Heavenly King’s third son, Prince Nezha, holds a pagoda and always follows the King.” His duty is to assist his father in safeguarding the Dharma, driving away evil forces, and protecting humanity. In The Mantra of the Dharma Protector Following the Northern Vaisravana Heavenly King, translated by the eminent Tang Dynasty monk Amoghavajra, Nezha is again referred to as Vaisravana’s third son. Other Buddhist texts from the Tang Dynasty, such as The Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana and The Lotus Sutra, also mention Nezha.

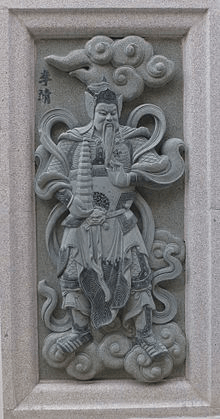

In Buddhism, Dharma protectors and yaksha deities often have fierce appearances, symbolizing their hatred of evil and fearless bravery. As a result, Nezha is typically depicted with a wrathful and intimidating image. As Buddhism spread to China, many Buddhist stories and figures gradually merged with local Chinese culture, giving rise to new belief systems. Over time, Nezha became integrated into Taoism and Chinese folk beliefs, forming a unique cultural phenomenon.

The story of Nezha is filled with many well-known and beloved episodes, such as his birth from a ball of flesh, cutting his flesh and bones to repay his parents, and being reborn from a lotus flower. Although this scene cannot be found in modern Buddhist scriptures, it became a popular topic among monks after the Song Dynasty. For example, Volume 1 of The Comprehensive Collection of Zen Verses on Ancient Cases mentions: “Prince Nezha offered his flesh to his mother and his bones to his father, then manifested his true form and used his divine power to preach to his parents.” This suggests that the story of Nezha sacrificing his flesh and bones likely originated from Buddhist texts. Although the exact cause and details are unclear, this story undoubtedly provided a prototype for later adaptations in folk literature.

As Buddhism spread throughout China, the assimilation of foreign religions by local culture and the evolution of folk beliefs gradually transformed Nezha’s image, steering it away from its original Buddhist context and toward a more Chinese identity. After the Tang Dynasty, the worship of Vaisravana (known as Bishamonten in Japan) reached its peak in China, gaining widespread recognition from both the imperial court and the common people. He was honored in official rituals and revered by many folk believers. Simultaneously, Li Jing, a prominent Tang Dynasty military general, became a popular figure of worship as a god of war. Renowned for his military campaigns against the Turks and Tuyuhun in the northwest, Li Jing was deified as early as the Tang Dynasty, with dedicated temples built in his honor during the Song Dynasty.

The broader and deeper the spread of a belief, the greater the possibility of its transformation and integration with other cultural elements. Over time, through public imagination and interpretation, the belief in Vaisravana merged with the worship of Li Jing, forming a new deity known as “Pagoda-Wielding Heavenly King Li” (Tuota Li Tianwang) by the Song Dynasty at the latest. From then on, Vaisravana took on the surname Li and became more secularized and localized within Chinese culture. Since Li Jing became identified with Vaisravana, it was only natural within folk beliefs to regard Nezha as Li Jing’s son. This marked Nezha’s departure from the cultural context of foreign religions and his integration into the Chinese pantheon.

This transformation made Nezha a more relatable and accessible figure, understood through the lens of native cultural concepts. As a result, Nezha’s story gained broader appeal, providing ample room for reinterpretation and adaptation in later generations.

Nezha holds an important place in ancient Chinese mythology. Under the influence of Taoism, he was endowed with more mythological attributes, portrayed as a young hero with powerful magical abilities who frequently battles demons and protects the people. His story further developed in classic literary works such as Journey to the West and Investiture of the Gods, where Nezha became a symbol of justice and courage.

Link:https://peacelilysite.com/2025/02/21/nezha-from-buddhist-origins-to-a-chinese-cultural-icon/