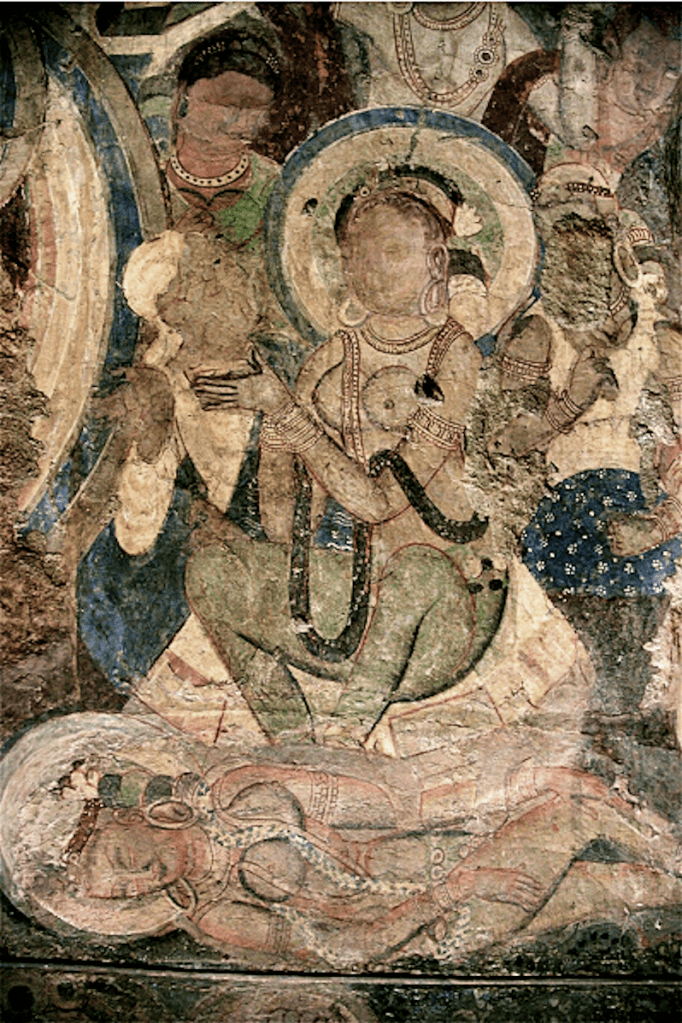

The Yungang Buddhist grottoes, a massive complex comprising 252 caves and niches with 51,000 statues carved into an area of 18,000 square meters, are a remarkable achievement of Buddhist cave art in China. Constructed from the mid-5th to early-6th century AD, the grottoes were influenced by Buddhist cave art from South and Central Asia but also incorporated distinct Chinese elements and local spirit. They played a crucial role among early Oriental Buddhist grottoes and had a far-reaching impact on Buddhist cave art in China and East Asia.

The five caves of Tanyao and their imperial patronage

The construction of Yungang began with five cave-temples, known today as caves 16 to 20, at the west end of the cliff. These caves were imperial commissions of the Northern Wei dynasty in around 460 C.E. The Northern Wei rulers, who belonged to the Tuoba clan from northern China, had recently unified northern China after centuries of political turmoil and established Buddhism as the state religion. The dynasty’s capital, Pingcheng, became a significant center for Buddhist religious and artistic expression.

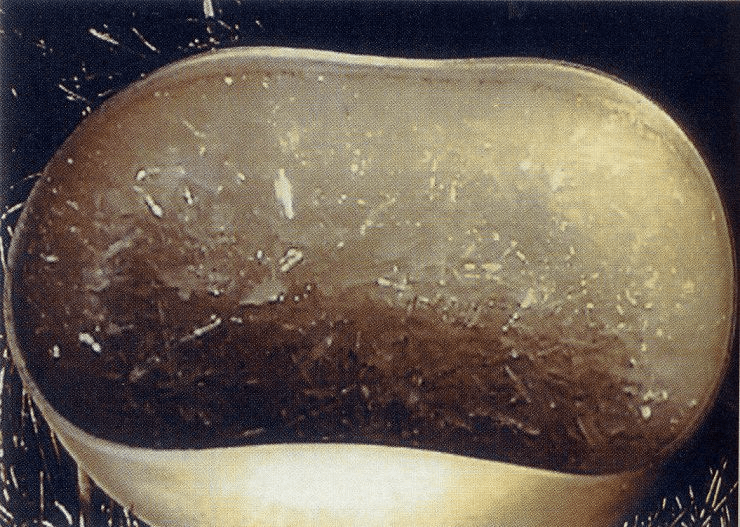

The five caves of Tanyao, created by Tan Yao, are classical masterpieces of the first peak of Chinese art, displaying a strict unity of layout and design. These caves each contain a colossal Buddha as the central icon, with Cave 20 housing a gigantic seated Buddha in a meditation posture and a standing attendant Buddha on one side. Another attendant Buddha likely existed on the other side, but it has been lost along with the cave’s exterior wall. The imperial patronage of these caves reflects the Northern Wei dynasty’s fusion of state power and religious devotion.

The main Buddha measures roughly 13 meters in height. He has plump cheeks, a thick neck, elongated eyes, a sharply cut nose, slightly smiling lips, and broad shoulders, all of which produce a solemn appearance.

The well-preserved halo behind the main Buddha is composed of an outer band of flame patterns and two inner bands decorated with seven seated Buddhas of miniature size. The robe features zigzag patterns on the edge. The right shoulder of the main Buddha is left exposed, whereas the standing attendant Buddha on the east wall wears a robe that covers both shoulders with a high neckline.

Historical records recount that Tanyao, a renowned monk cleric with official ranks, advised Emperor Wencheng to undertake construction of five cave-temples (Caves 16–20) to commemorate the five founding emperors of the Northern Wei dynasty. Claiming that the emperor of Northern Wei was the living Buddha, this project declared the emperor’s political and spiritual legitimacy, and strengthened the rule of the imperial family.

Buddha (left) and attendant Buddha (right), Cave 20 at Yungang (photo: xiquinhosilva, CC BY 2.0)

The statues housed in the caves and niches are in good condition and all of the caves and statues have not suffered major damage from vandalism and/or natural disasters. Restoration and repair had been made on deficient parts of some statues in the past. All the necessary attributes demonstrating the Outstanding Universal Value of Yungang Grottoes are contained within the boundary of the property area. The buffer zone provides a necessary safe area for the conservation of the Grottoes, the setting and the historic environment. These measures have enabled the Yungang Grottoes to serve as one of the greatest ancient stone carving art treasure houses in the world.

The location, caves and statues of the Yungang Grottoes have retained their historic appearance. The eaves of wooden pavilions of the caves and the related historical remains have kept the distinctive character of the times when they were constructed. The daily maintenance and conservation intervention have been conducted following the conservation principle of minimal intervention in design, materials, methodology, techniques and craftsmanship.

The paired caves and the major development at Yungang

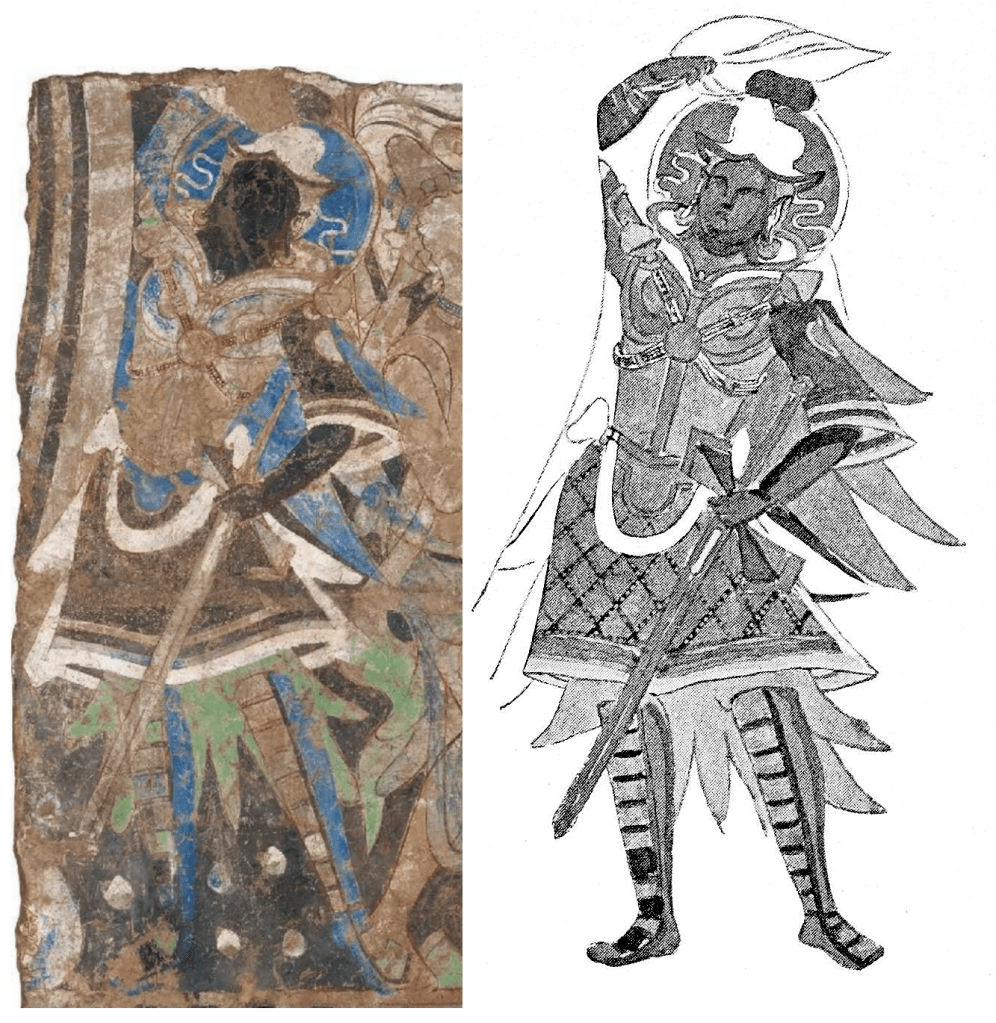

Beginning roughly a decade after the initial commission, the imperial projects at Yungang advanced to a second phase that lasted from c. 470s until 494 C.E. In contrast to the monumental Buddha found in Cave 20, the interior of the second-phase cave-temples are decorated with reliefs that depict Buddhas, bodhisattvas, and other divine figures in various scales and configurations.

One of the most distinctive features developed in the second phase of construction are paired caves—two adjacent caves featuring a similar architectural plan and pictorial program. The paired cave-temple layout is understood to symbolically represent the reign of two coincident rulers: Emperor Xiaowen (471–499 C.E.) and Empress Dowager Wenming (442–490 C.E.). The use of paired cave-temples became another means to demonstrate the dynasty’s imperial power.

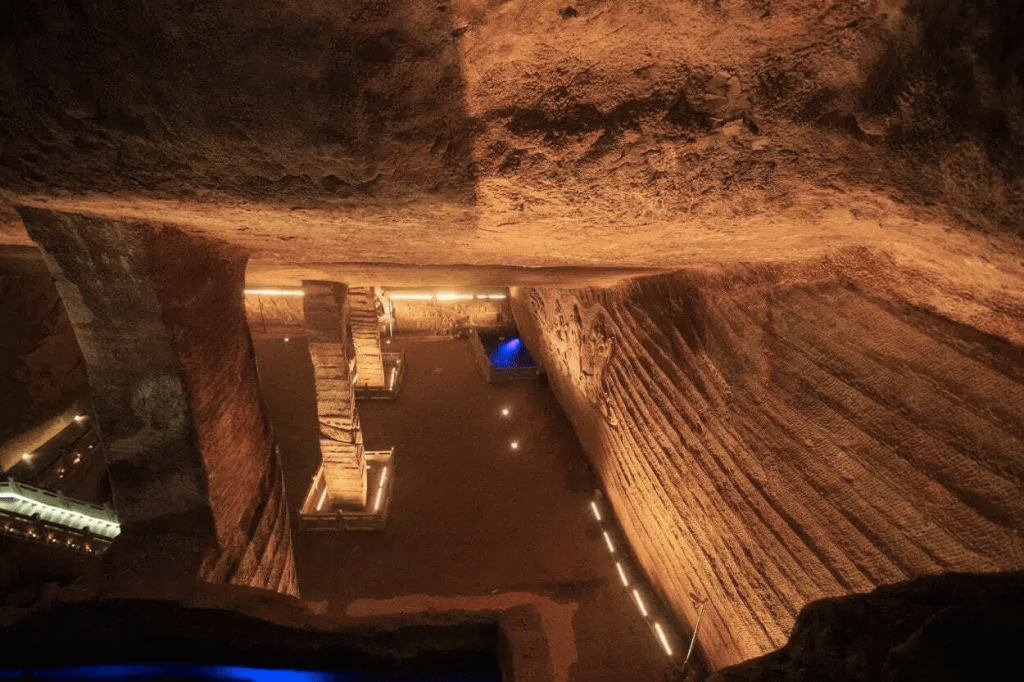

The paired Caves 5 and 6 are among the most lavishly decorated cave-temples at Yungang. Cave 6 has an antechamber and a square main chamber supported by a central pillar (see the full cave 6 in 3D). A square clerestory (window) is opened right above the passageway to the main chamber to let in light (although it is hard to see in photos or the 3D image).

In the main chamber of Cave 6, the east, south, and west walls are divided vertically into three main registers that include complex pictorial programs (the north wall features a large niche housing a trinity of Buddhas that are later repairs). We find seated Buddha figures and scenes from the Buddha’s life throughout the chamber. Depictions of the historical Buddha, who was believed to live in the Ganges River basin during the 6th century B.C.E., derived largely from Buddhist texts. The Buddha’s biography details the course of his life from birth to enlightenment, and eventually to nirvana, the final extinction. The life of the Buddha was among the most popular themes for artistic representation throughout the Buddhist world.

One scene from the Buddha’s life (at the southern end of the east wall) shows the First Sermon of the Buddha at Deer Park, identifiable by the depiction of a pair of deer on the Buddha’s throne. We see a canopied standing Buddha flanked by two standing bodhisattvas and a myriad of worshippers in the background. Just below the standing Buddha niche, a seated Buddha with his right hand raised (the fearless gesture) can be seen in a trapezoidal-shaped niche flanked by two five-story pagodas (just visible at the edges of the scene in the photograph). Worshippers either kneel in front of the throne or stand facing the Buddha on his two sides.

Rock-cut cave-temples

Rock-cut cave-temples first appeared in western India in the 1st century B.C.E. There are two basic types: apsidal-shaped (semicircular) chaitya (sanctuary, temple, or prayer hall in Indian religions) and vihāra caves where monks resided—both of which we find at places like the caves of Ajanta, India. Both types were transmitted eastwards to Central Asia up to the 5th century with modifications of the structures. At Yungang, the sanctuary type was further adapted into a square shape that houses a central pillar in the middle, as we find in Cave 6. At the same time, a number of architectural features find their precedents in Goguryeo tombs from present-day northeastern China and North Korea.

But what facilitated these different traditions coming together at Yungang?

Transmissions and transformations of artistic styles

Yungang was a hub where multiple artistic traditions of South Asia, Central Asia, and pre-Buddhist China synthesized into something new. This was made possible by the Silk Road, a network of ancient trade routes linking East Asia with the rest of Eurasia. Goods and ideas have been exchanged along the Silk Road since at least the second century B.C.E. Central to the economic, cultural, and religious interactions between different parts of Eurasia, the Silk Road tied the Northern Wei territory to the sacred heartland of Buddhism in South Asia, and to Central Asian kingdoms that promoted Buddhist teachings.

A primary factor facilitating the encounter of these varied traditions was the gathering of human resources and materials from different regions. In the 430s and 440s, the Northern Wei court issued decrees that relocated artisans and monks from its conquered lands to the capital city of Pingcheng. The concentration of people and craftsmanship in the capital led to the artistic flourishing of well-executed Buddhist monasteries, cave-temples, sculptures, and murals. Eminent monks who were active in Pingcheng had also engaged with religious activities in other urban centers such as Chang’an and Wuwei, and maintained close ties with Central Asian Buddhist communities.

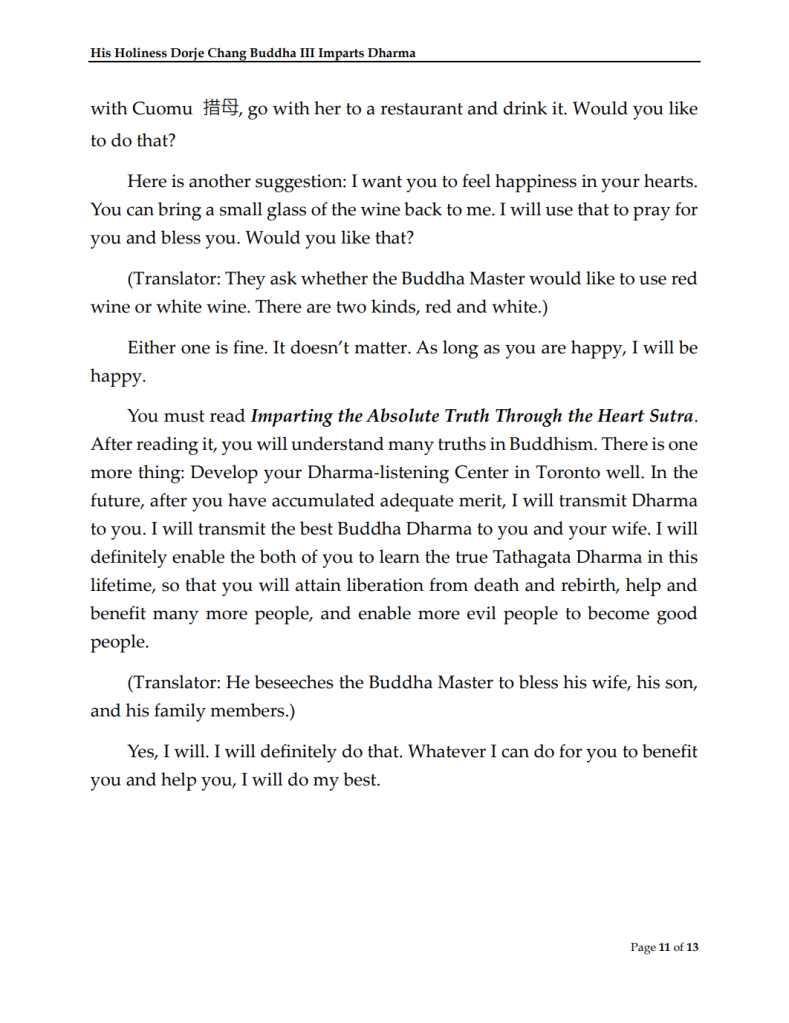

Just as the form of the rock-cut cave-temples was adapted from earlier traditions in South Asia, statues and reliefs at Yungang exhibit strong stylistic and iconographic affinities with earlier Buddhist art traditions from northwestern India and Central Asia. For instance, the main colossal Buddha images in Caves 16 to 20 feature a round face, with a gentle, calm expression that creates an impression of sanctity, and a robe style that clings tightly to the body yet is rendered with schematic patterns. All of these features echo the aesthetics found in previous traditions, especially the Buddhist sculptures in Gandhara, a Buddhist center located in present-day northwest India and Pakistan.

Yungang art exerted influence, in turn, on Central Asian cave-temples starting in the later 6th century, such as Dunhuang, indicating that a dynamic exchange took place among the major cultural centers along the Silk Road.

Sinicization reforms under the reign of Emperor Xiaowen

One of the new developments shown at Yungang that would have a long-lasting effect on Chinese Buddhist art was Sinicization, a process of adapting non-Chinese traditions into Han Chinese culture. In Cave 1, between the canopy of the central pillar and the ceiling we find intertwined dragons surrounding mountains that represent Mount Meru (the sacred mountain considered to be the center of the universe in Buddhist cosmology). The design shows strong influence of the pre-Buddhist Chinese tradition in two aspects. First, the dragons are depicted with typical Chinese conventions—a snake-like curving body with four legs. Mount Meru was not related to dragons in pre-Chinese Buddhist art traditions. The incorporation of dragons in the design reveals an integration of the motif’s symbolic reference to a spiritual life force in traditional Chinese beliefs.

In Cave 6, we also see Sinicized traits in a new style of the Buddha’s monastic robe, which features loose drapery that falls around the body and clothes the Buddha entirely instead of the earlier style that clings closely to a partly exposed body. The new style finds parallel in the contemporary dress of court officials.

Overall, these new styles and motifs were a response to the political reform of Sinicization promoted by Emperor Xiaowen and Dowager Wenming during their reign in the Taihe era (477–499 C.E.). The reform aimed at legitimizing the Northern Wei regime, built by non-Chinese nomadic groups, as an imperial Chinese dynasty, and promoting a greater sense of conformity throughout the empire.

The legacy of Yungang

Despite the move of the capital to Luoyang in 494 C.E., constructions at Yungang continued for another three decades. Cave-temples of this phase are much smaller in size than at the earlier western end of the complex. Over half a millennium later in the 13th century when Yungang was the capital of the Liao Dynasty, Yungang witnessed another era of glory, with restorations of the caves and installation of wooden structures attached to their façades. Yet it was only a temporary phenomenon. The site later stayed silent for centuries until its early 20th-century rediscovery along with other major cave-temples by foreigners on expeditions.

Modern scholarship about the history and the art of Yungang Cave-temples has continued to provide new information about the site. The most recent archaeological excavations at Yungang unearthed the remains of a monastery dated to the Northern Wei dynasty above the western section of the cliff. The well-preserved foundations of courtyards, the central stupa (a sepulchral monument that refers to the Buddha), residential cells for monks, and objects continue to enrich our understanding of the site as a significant religious center from the 5th century.

Link: https://peacelilysite.com/2023/03/31/yungang-grottoes/

#BuddhistArt #YungangGrottoes #BuddhaStatus #Buddhist #SilkRoad #TravelChina #BuddhistHistory #Cave-Temples #Religion

Source: smarthistory.org/yungang-grottoes