The Buddhist concept of cause and effect (karma) is truly an unfathomable truth

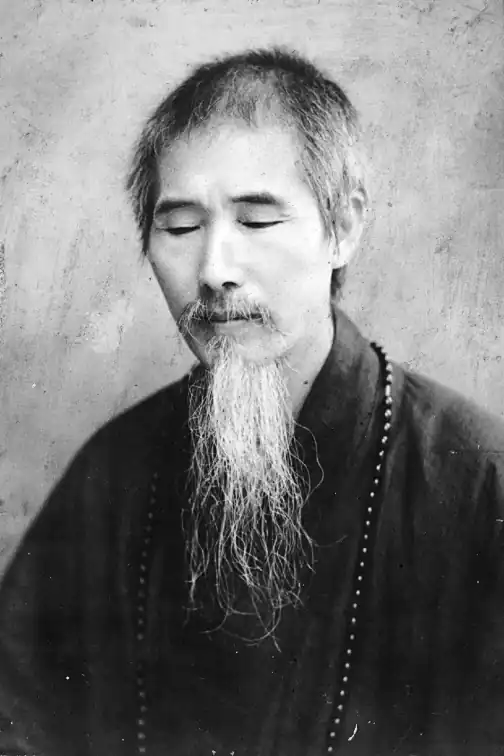

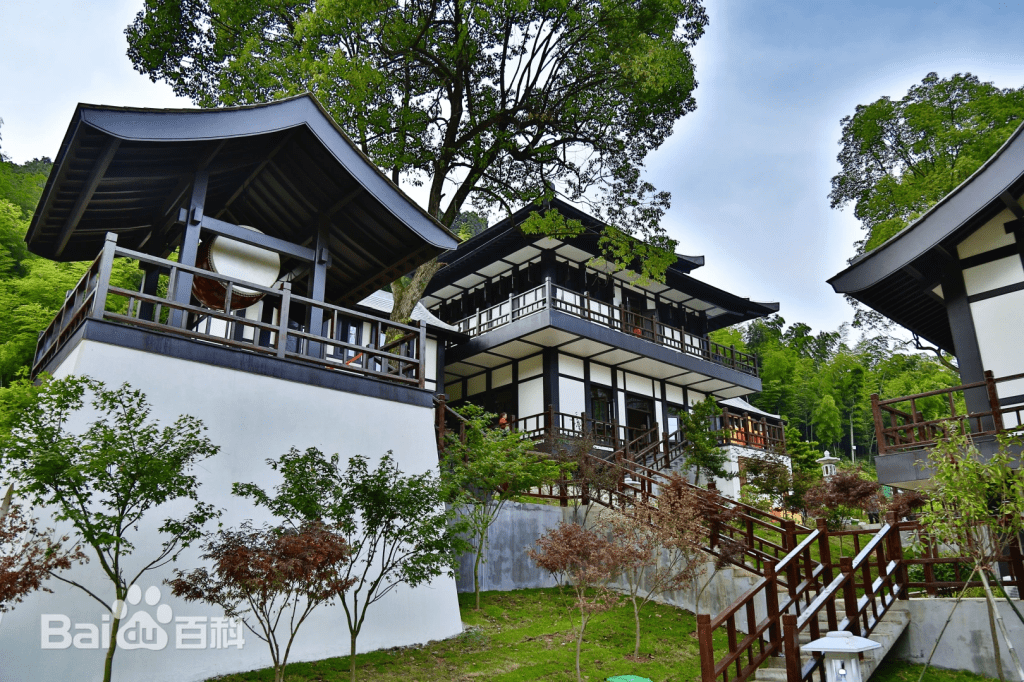

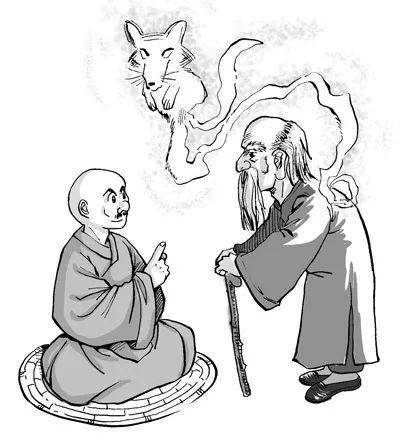

Long ago, deep in the mountains, there lived a Zen master named Wuguo(无果), a practitioner wholly devoted to meditation. For more than twenty years, he was supported by a humble mother and daughter who offered him food and daily necessities so he could cultivate the Way without distraction.

As the years passed, Master Wuguo reflected deeply on his practice. Although he had dedicated his life to meditation, he felt he had not yet realized his true nature. A quiet fear arose in his heart: If I have not awakened, how can I truly repay the kindness of these offerings?

Determined to resolve the great matter of life and death, he decided to leave the mountain to seek instruction from other masters.

When the mother and daughter heard of his departure, they asked him to stay a few more days. They wished to sew him a monastic robe for his journey. At home, the two women worked carefully, chanting the name of Amitabha Buddha with every stitch, their hearts filled with sincerity. When the robe was finished, they also wrapped four silver ingots to serve as his travel funds.

Master Wuguo accepted their offerings and prepared to leave the next morning.

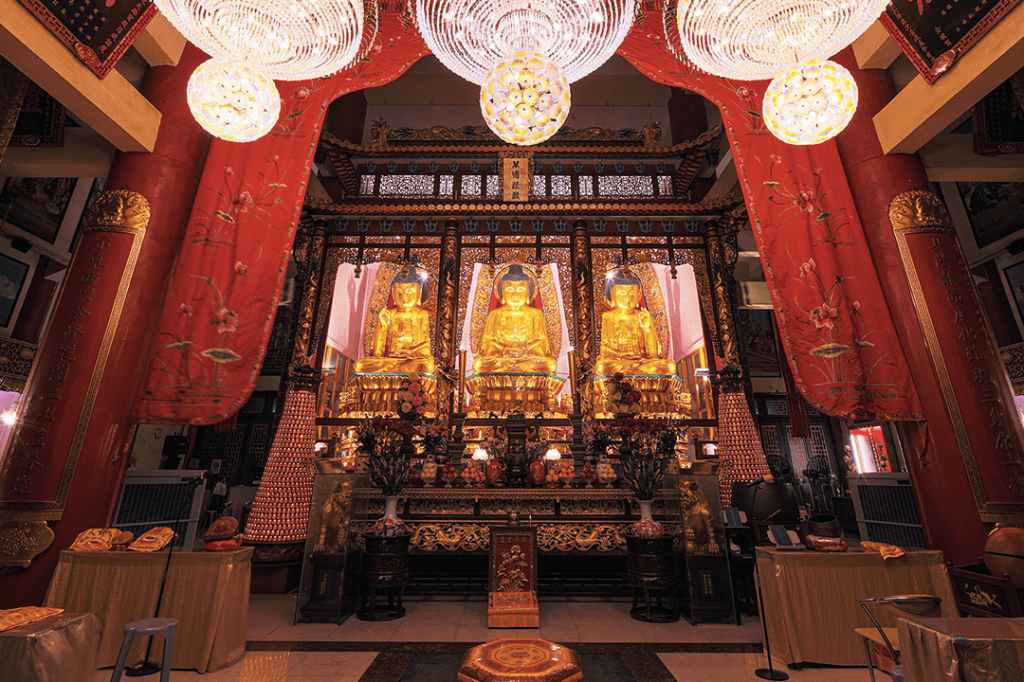

That night, as he sat quietly in meditation, a vision appeared. A young man dressed in blue stood before him, holding a banner. Behind him came a procession playing music and carrying a magnificent lotus flower.

“Zen Master,” the youth said, “please ascend the Lotus Seat.”

Master Wuguo remained calm. He reflected inwardly: I am a Zen practitioner, cultivating meditative concentration. I have not practiced the Pure Land path. I should not become attached to visions. Even for a Pure Land practitioner, such an experience could be a delusion.

He ignored the vision.

Yet the youth returned again and again, urging him earnestly not to miss this rare opportunity. Finally, Master Wuguo picked up his small hand-bell (yinqing) and placed it on the lotus seat. Soon after, the youth and the entire procession vanished.

The next morning, as Master Wuguo prepared to depart, the mother and daughter hurried toward him in distress. Holding the hand-bell, they asked anxiously:

“Master, is this yours? Something very strange happened last night. Our mare gave birth to a stillborn foal. When the groom cut it open, he found this bell inside. We recognized it immediately and rushed to return it—but we cannot understand how it came from a horse’s belly.”

Upon hearing this, Master Wuguo broke into a cold sweat. Deeply shaken, he composed a verse:

One monastic robe, one sheet of hide;

Four silver ingots, four hooves inside.

Had this old monk lacked the power of Zen,

Your stable is where I would have been.

In that moment, he clearly understood the law of cause and effect. By accepting the robe and the silver, he had created a karmic debt. Had his mind been even slightly attached—to the vision, to the offerings, or to the idea of reward—he would have been reborn as a horse in that very household, laboring to repay what he had received.

Immediately, Master Wuguo returned the robe and the silver to the women and departed.

Because he did not cling to extraordinary visions, he escaped rebirth in the animal realm. An ordinary person, upon encountering such sights, would have grasped at them, fallen into delusion, and continued revolving in the cycle of rebirth.

This story reveals a profound truth: the realms are not distant places—they arise from the mind itself.

When the mind dwells in craving and greed, it becomes the realm of the Hungry Ghosts, endlessly desiring yet never satisfied.

When the mind dwells in anger and resentment, it becomes the Asura realm, filled with conflict and struggle.

When the mind is clouded by ignorance and confusion, it sinks into the Animal realm, driven by instinct and karmic habit.

In our daily lives, we often fixate on external things—lust, fame, wealth, comfort, indulgence—believing we cannot live without them. Yet we fail to see that all phenomena arise from causes and conditions. When conditions gather, things appear; when conditions disperse, they vanish. None possess a fixed or permanent essence.

Reflect carefully:

Is there anything in this world we can truly hold onto forever?

Since nothing produced by conditions can be owned, lasting happiness cannot be found through possession or attachment. True happiness arises from non-attachment, from seeking nothing and clinging to nothing. When the mind releases its grasp, it becomes light, clear, and free.

So we may ask ourselves:

Can we remain at peace amid changing emotions?

Can we stay calm in the face of conflict?

Can we remain unmoved by fame and profit?

And when the moment of death arrives, can our mind remain clear and mindful?

The law of cause and effect never errs.

What we cultivate in the mind today shapes the world we inhabit tomorrow.

Link:https://peacelilysite.com/2026/01/07/the-bell-in-the-horses-belly/