At late Qing Dynasty, during the reign of Emperor Guangxu, there was a true story that took place:

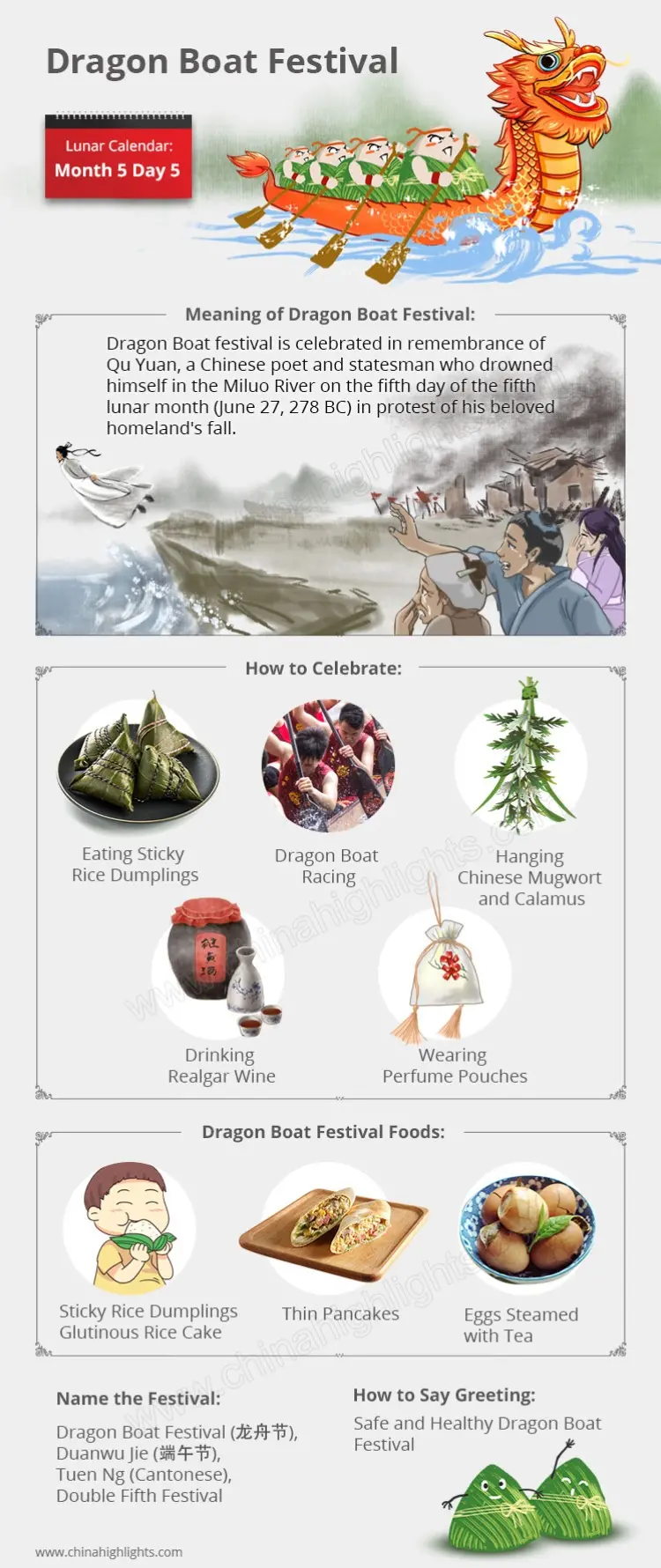

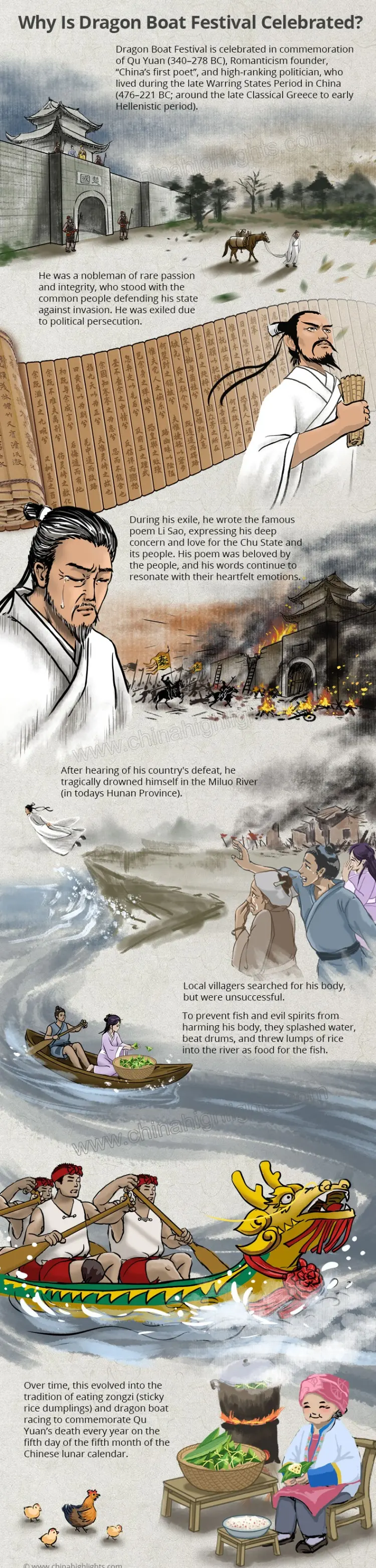

Mr. Jia from Jiangsu worked for a foreign trading company in the Shanghai concession. He had earned the deep trust of his employer. Just before the Dragon Boat Festival, his boss sent him south of the city to collect debts. With a leather money pouch in hand, Mr. Jia set off.

The collections went smoothly, and by noon he had received more than 1,800 silver dollars. After walking and talking all morning, he was parched and exhausted. Passing by the famous Shiliupu teahouse, he hurried inside for a quick cup of tea before rushing back to deliver the money and finally rest.

When he returned to the company, he suddenly realized—the leather pouch was gone. Thunderstruck, drenched in sweat, and nearly fainting, he could not explain himself clearly in his panic.

Seeing his flustered state, the boss grew suspicious, believing Jia might be dishonest. He harshly rebuked him for betraying trust, warning that if the money was not returned quickly, Jia would be handed over to the authorities.

At that time, 1,800 silver dollars was a fortune—enough for a person to live on comfortably for a lifetime if carefully spent. How could Mr. Jia ever repay such a sum? With his reputation and life on the line, he felt utterly ruined and broke down in despair.

Meanwhile, in another part of the concession, a merchant from Pudong, surnamed Yi, had recently lost all his money in business. Discouraged, he bought a boat ticket for that very afternoon to return home across the river.

With time to spare before boarding, Mr. Yi also went to Shiliupu teahouse, intending to sip tea slowly while pondering his uncertain future.

By coincidence, just as Mr. Jia had hurried out, Mr. Yi walked in. As he sat down, he noticed a small leather pouch left on a chair. He paid it little mind at first and began drinking tea.

After some time, no one came to claim it. Curious, he lifted it and felt its weight. Opening it, he nearly dropped it in shock—inside was a fortune in gleaming silver coins!

At first he was overwhelmed with joy. Such a windfall could end his misfortune and secure a comfortable life. But then he thought: No, money belongs to its rightful owner. If I keep it, the loser may be ruined, disgraced, or even driven to death. The sin would be unbearable.

In those days, most decent people knew the saying: “Ill-gotten wealth must not be taken.” Mr. Yi resolved: Since fate placed this money in my hands, I have the responsibility to return it.

At lunchtime, only eight or nine guests remained in the teahouse. None appeared to be searching for lost money, so Yi, hungry as he was, decided to keep waiting.

By evening, as lamps were being lit, the teahouse emptied out—only Mr. Yi remained, watching the entrance intently.

Suddenly, he saw a pale, staggering man rush in, followed by two companions. It was Mr. Jia. As soon as he entered, Jia pointed at Yi’s table and cried, “There! That’s where I was sitting!” The three came straight toward Yi.

Yi smiled and asked, “Are you looking for a lost pouch?”

Jia stared in disbelief and nodded repeatedly. “I’ve been waiting for you,” Yi said, producing the leather pouch.

Overcome with relief, Jia trembled all over. “You are my savior! Without you, I would have hanged myself tonight!”

It turned out that when Jia had discovered the loss, he had begged to retrace his steps, though he knew recovery was unlikely. His boss, fearing he might flee, initially forbade it. After much pleading, the boss finally allowed him to go, but only under the close watch of two escorts, who were ordered to bring him back regardless of the outcome.

After exchanging names, Jia gratefully offered Yi a fifth of the money as a reward. Yi firmly refused. Jia lowered it to a tenth, then to a hundredth—Yi grew angry and sternly declined.

Flustered, Jia said, “Then at least let me treat you to a drink!” Yi still refused. Finally Jia pleaded, “If I cannot show gratitude, my conscience will not rest. Tomorrow morning, please allow me to host you at such-and-such tavern. I beg you to come—without fail.” Bowing deeply, he left.

The next morning, Yi did indeed appear. Jia was just about to bow in thanks when Yi quickly interrupted, saying:

“Actually, it is I who should thank you. If not for your lost pouch, I would not be alive today!”

Puzzled, Jia asked what he meant. Yi explained:

“Yesterday, I had bought a one o’clock boat ticket to return home. But because I waited in the teahouse to return your money, I missed the departure. When I finally returned to my lodging, I learned that the boat had capsized midway in a violent wave. All 23 passengers drowned. Had I boarded, I too would be dead. So you see, it was you who saved my life!”

The two men, overwhelmed, bowed to each other in tears.

Onlookers marveled, toasting the pair. They said Mr. Yi’s single good deed had saved not just Jia’s life, but his own as well.

The story did not end there. When Jia and his escorts returned and reported everything, the boss was astonished. “Such a virtuous man is rare indeed!” he exclaimed, insisting on meeting Yi.

The two met and felt an immediate bond. After a long conversation, the boss earnestly invited Yi to stay, offering him a high salary to manage accounts. Months later, he even married Yi into his family as a son-in-law. In time, the boss entrusted the entire business to him.

“Cause and effect of good and evil” is absolutely true, without the slightest mistake. Goodness nurtures more goodness, and goodness attracts goodness. To treat others with kindness is, in fact, to accumulate blessings and good fortune for oneself. A human life is not lived for just a fleeting moment. The speed of temporary gains or losses, the ups and downs of a single day, even honor or disgrace in the short term—none of these truly matter. Today’s kindness becomes tomorrow’s blessings. Today’s evil leads to tomorrow’s misfortune. Time is a great author, and it will always write the perfect answer.

Therefore, simply be a good person, and the future will be full of hope. Do good deeds, and the road ahead will surely be bright and promising.

Link:https://peacelilysite.com/2025/08/29/youll-never-guess-why-he-survived/