Shanxi is often called the cradle of Chinese civilization, a province with one of the richest collections of cultural and historical relics. Guangsheng Temple is part of that story. First built during the Eastern Han Dynasty (25–220 CE), it is one of the earliest Buddhist temples in China. Over the centuries, it has endured wars, fires, and devastating earthquakes, yet it still stands, its beauty renewed through reconstructions in the Yuan (1271–1368) and Ming (1368–1644) dynasties.

The temple complex is composed of three main parts:

- The Upper Monastery — home to its most famous landmark, the glazed pagoda.

- The Lower Monastery — housing grand halls and statues.

- The Water God Temple — known for its remarkable Yuan Dynasty murals.

Rising in the upper monastery is the Flying Rainbow Pagoda (Feihongta), an octagonal, 13-story glazed brick tower reaching 47.31 meters high. Built in 1527 during the Ming Dynasty, it’s an explosion of color in the sunlight. The walls and roofs are covered in multi-colored glazed tiles — deep emerald, golden yellow, sapphire blue, and rich purples — that glisten like jewels, casting rainbow-like reflections on sunny days.

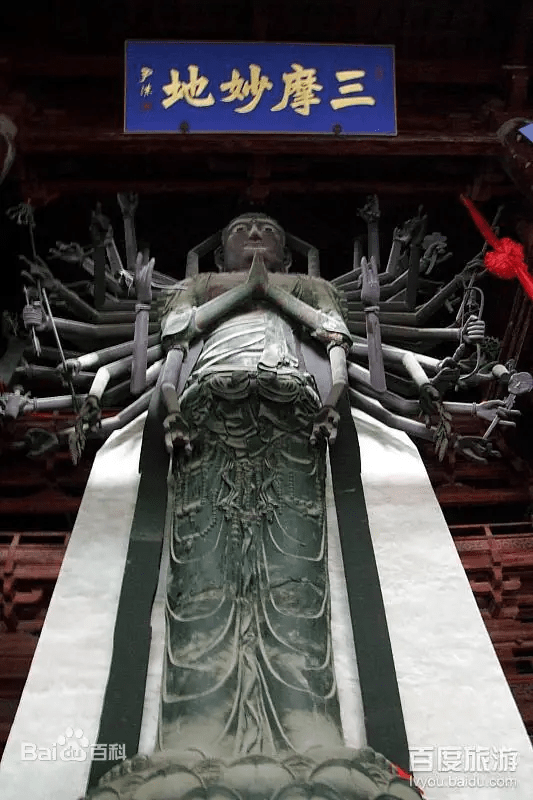

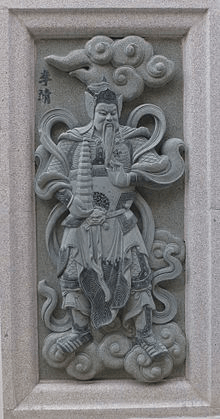

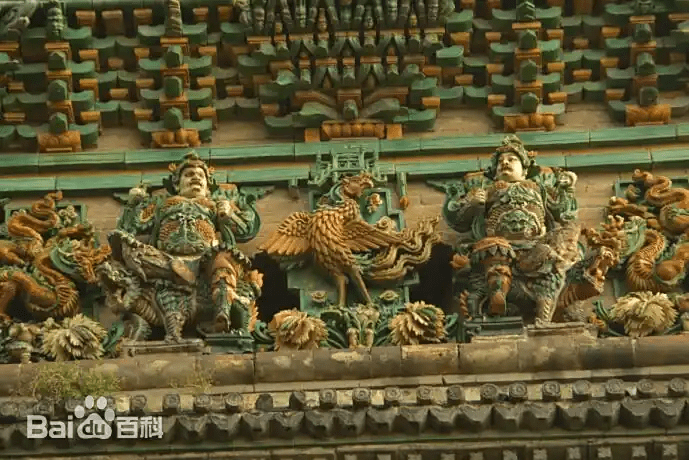

Every tier of the pagoda is adorned with intricate glazed reliefs — Buddhas in serene meditation, fierce guardian kings, bodhisattvas in flowing robes, mythical beasts, and dragons coiled in eternal motion. Inside, the foundation hall houses a five-meter-tall bronze statue of Sakyamuni Buddha, radiating quiet majesty.

This pagoda is not only beautiful — it’s a survivor. It withstood the catastrophic 1556 Shaanxi earthquake and the 1695 Pingyang earthquake, both exceeding magnitude 8.0. Its resilience is as awe-inspiring as its artistry. In 2018, it was recognized by the London-based World Record Certification as the tallest multicolored glazed pagoda in the world.

Murals of the Yuan Dynasty — Life Painted in Color

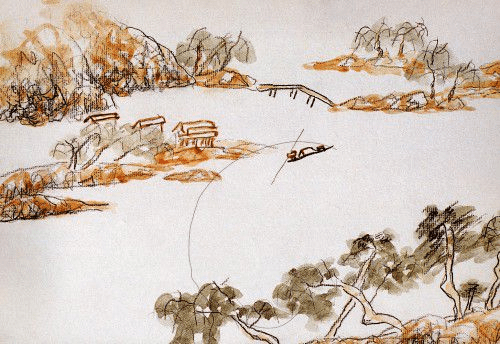

The temple’s murals are a vivid window into the Yuan Dynasty. In the Water God Temple, nearly 200 square meters of wall space is alive with color: scenes of divine processions, farmers at work, musicians playing, and children at play. One remarkable panel shows “Cuíwán” (捶丸) — a sport similar to golf — offering a glimpse into pastimes of the Yuan era.

The mural on the gable wall of the Great Hall of Sakyamuni Buddha in the lower monastery is equally stunning, painted with an expressive style that blends religious devotion with snapshots of daily life. Researchers prize these works for their artistry and for the wealth of cultural detail they reveal — clothing, architecture, social customs — all preserved in pigment for more than 700 years.

The Zhaocheng Buddhist Canon — A Literary Treasure

In 1930, during restoration work, the temple revealed another extraordinary surprise—a cache of ancient relics now preserved in the Shanxi Museum. These included Buddhist scriptures, statues, and ritual objects, some dating back hundreds of years earlier. Printed during the Yuan Dynasty, this monumental project took 24 years and the collaboration of countless monks and artisans to engrave the wooden printing blocks. The texts preserve Buddhist thought, philosophy, and art from centuries ago, making them one of China’s most precious Buddhist literary relics.

The discovery deepened Guangsheng Temple’s reputation as one of the great guardians of China’s Buddhist heritage.

Today, whether you approach as a pilgrim, an art lover, or simply a traveler drawn by curiosity, the moment you first see the rainbow-like shimmer of the Glazed Pagoda through the mountain mist is unforgettable. It is not merely a structure—it is a bridge between centuries, a beacon of faith, and a reminder that beauty, once created with devotion, can endure against time itself.

Link: https://peacelilysite.com/2025/08/15/guangsheng-temple-the-hidden-gem-of-shanxis-ancient-treasures/

Source: http://shanxi.chinadaily.com.cn/2022-05/06/c_748899.htm?utm_source=chatgpt.com