Nestled in the heart of Xinjiang, the Turpan Basin holds several extraordinary records: it’s the lowest geographical point in China, and during summer, it’s the hottest place in the country. With scorching sunlight, relentless winds, and almost no rainfall, Turpan earns its title as the “Land of Fire.”

In the peak of summer, the surface temperature in the surrounding Gobi Desert can soar to 82.3°C (180.1°F), while the air temperature often exceeds 49°C (120°F). Rain is almost nonexistent—Turpan receives an average of just 16.4 mm of rainfall annually, and in some years, as little as 4.3 mm. Yet, amidst this harsh, parched environment, an ancient miracle has quietly sustained life for over two thousand years: the Karez irrigation system.

A Miracle Beneath the Earth

While nature was unforgiving above ground, it hid a gift below. Meltwater from the distant Tianshan Mountains seeps underground through coarse gravel and sand, eventually blocked by the Flaming Mountains and surfacing as springs. Ingenious local people found a way to capture and guide this underground treasure—thus, the Karez was born.

The Karez system channels water from mountain sources through a network of underground tunnels and vertical shafts, delivering it to the arid land without evaporation loss. Remarkably, this ancient system operates entirely without pumps, relying solely on gravity and terrain.

A complete Karez includes:

- Vertical shafts for ventilation and maintenance

- Underground tunnels to carry water

- Open canals to distribute it

- Storage ponds to hold it

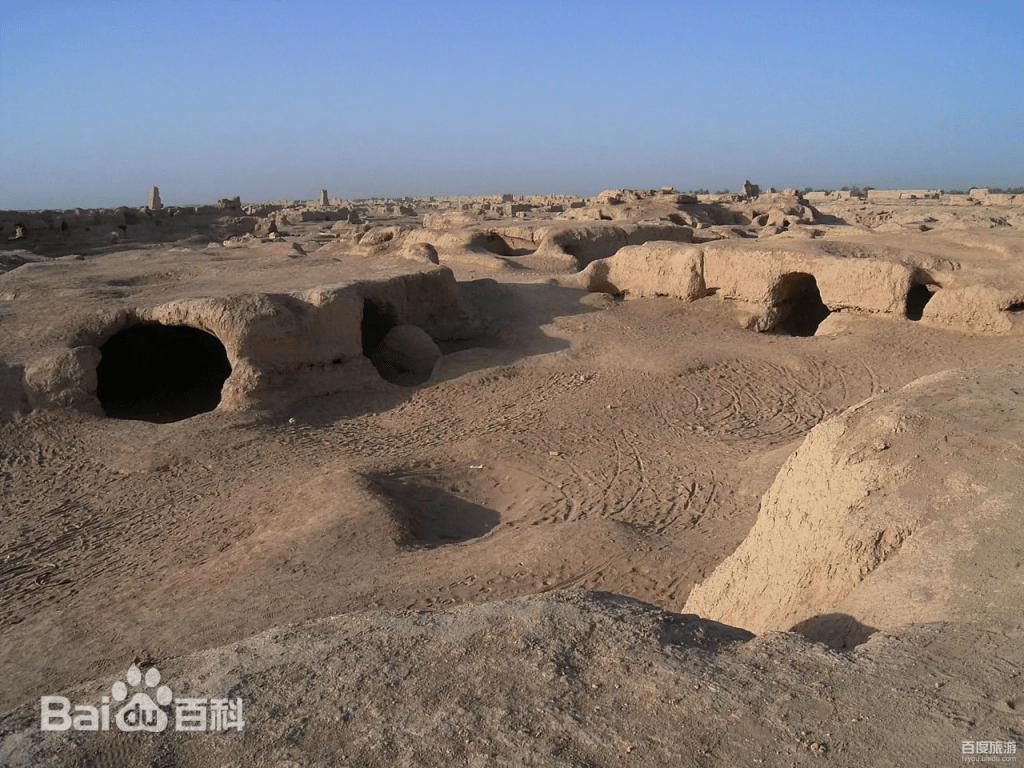

Across Turpan’s landscape, you can still see long rows of small mounds—each one marking a shaft, a glimpse into the remarkable infrastructure below.

A Testament to Ingenuity and Endurance

The origins of the Karez can be traced back to the Han Dynasty, over 2,000 years ago. Most of the surviving systems were built during the Qing Dynasty, including during historical moments like Lin Zexu’s fourth inspection of Turpan, when over 300 new Karez channels were added, and Zuo Zongtang’s campaigns, which saw nearly 200 more constructed.

At its peak in the 1950s, there were about 1,700 Karez systems in Turpan, stretching over 3,000 kilometers. Today, about 725 remain, a number slowly dwindling due to modernization, drought, and human impact.

The construction of each Karez was no small feat. Generations of laborers worked in dark, narrow tunnels, often barefoot in icy water, chiseling stone with simple tools and oil lamps. They carried earth and rock out by hand, surviving on dry flatbread and enduring brutal conditions.

A Culture of Water, Wisdom, and Survival

More than just a hydraulic system, the Karez represents a culture—a story of human resilience, harmony with nature, and intergenerational wisdom. In this water-scarce land, the Karez has nurtured lush vineyards, fertile fields, and diverse communities, offering life where none should thrive.

Today, many of these systems are dry or abandoned, relics of a past shaped by necessity and brilliance. But for those who walk among them, they are still very much alive—whispers from the earth, reminding us of what is possible when people respect and work with nature.

If you ever find yourself in Turpan, do not miss the chance to explore the Karez wells. They are more than ancient engineering marvels—they are monuments of perseverance, and living echoes of a civilization that made the desert bloom.